“Endgame” by Omid Scobie has stirred significant controversy upon its November book release. Apart from the backlash against the publication itself, the Dutch version was pulled after reports surfaced that the identity of the royal who allegedly made racist comments about Meghan Markle and Prince Harry’s child had been revealed. But beyond this uproar, the book is essentially an extension of Prince Harry’s memoir, “Spare,” which was published earlier this year.

Read: Omid Scobie: Endgame Dutch book pulled over race comment error

What it describes is an existential problem within the royal family itself, where it heavily relies on leaks, sources, and hearsay to maintain the facade of divine rule. Unfortunately, journalist Scobie falls into the same trap as many other books about the Firm, even though he attempts to distance himself from the toxicity of internal backstabbing. However, the contentious book highlights the fact that without the constant media rhetoric and the general tit-for-tat nature between journalists and the royal household, the royal family may cease to survive.

Endgame book and the royal media web

In the 400-plus page book, the word “source” appears 148 times, underscoring the issue of what is essentially superficial gossip. These informants aren’t whistleblowers in the same way; there are very few repercussions for their actions, and instead, many are treated like loyal servants. So, why are we listening to them? This extends to all royal correspondence, to the extent that even conservative BBC journalist Andrew Marr has said, “Either well-known journalists are making a lot of stuff up, just sitting at their laptops at the kitchen table inventing the detail of feuds and private confrontations, or a particularly confidence-rotting form of anonymous briefing has been taking place.”

While the book itself is fairly sparse in its revelations, often reiterating what has been said in previous works and newspapers, it sheds light on the fundamental issue of the dangerous game between different institutions. After all, isn’t the press supposed to be independent of the government and, by extension, the royal family, which serves as the head of state? Most of the blame can be squarely attributed to the fact that this symbiotic relationship has begun to blur the lines, making it difficult to distinguish where one entity begins and the other ends.

The changing face of royal communication

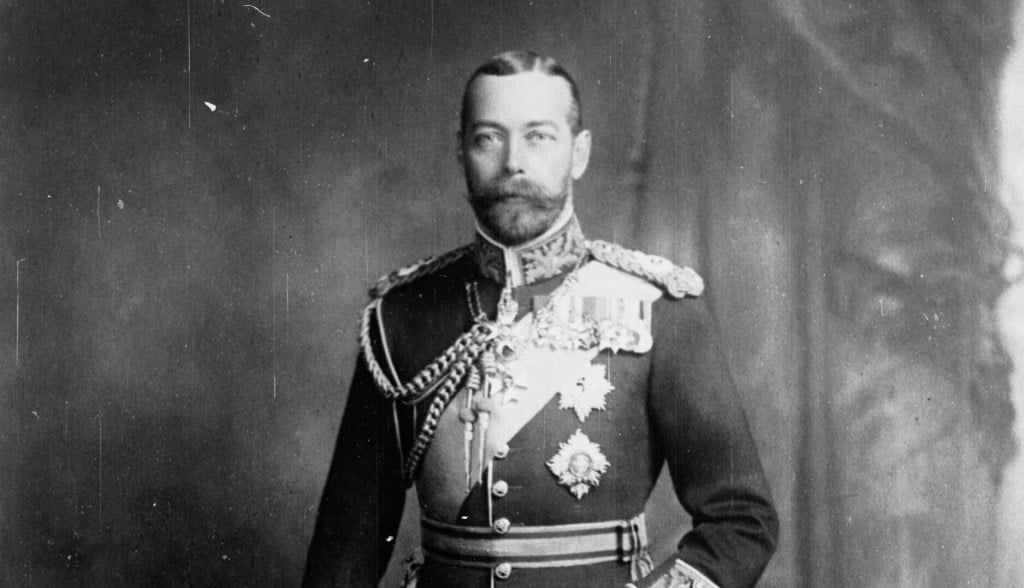

British monarchs have been delivering speeches for centuries, but it wasn’t until the 20th century, with the emergence of radio technology, that they could address the entire nation simultaneously through the media. On December 25, 1932, King George V marked a historic moment as he became the inaugural British monarch to deliver a live radio broadcast to the entire nation on Christmas Day. Then, BBC director-general Lord John C. W. Reith persuaded the late king to give the broadcast, as the Empire began to wane, and the importance of reaching the entire white populace of the colonies became significant. Reith stated: “For all the talk of Empire unity, the Dominions always wanted to go their own way, and control of broadcasting seemed almost to be a test case of national sovereignty.”

According to the official Buckingham Palace website, King George V initially had reservations about employing the relatively untested medium of radio to communicate with the public, as he believed it was mainly for entertainment. However, after a visit to the BBC, he was reassured and gave his consent to participate. Consequently, King George V addressed the entire Empire through the “wireless” from a modest office at Sandringham for the first Christmas broadcast.

Read: Are memoirs still important? Top books and why we love them

Since then, the issue of accessibility has been thrust into the limelight even more, especially as colonial powers deteriorated, and the once-mighty empire was consigned to the ash heap of history. With this emerging reality, it has become apparent that to gain favour with the royal household, one must print whatever they are told without subjecting the claims to scrutiny. Moreover, it has become evident that the sovereign must stay relevant to ensure their longevity in the foreseeable future.

Navigating anonymous sources, gossip, and the search for reliable information

Some of the key players in this imperial charade are the “courtiers,” better known as private secretaries. Scobie believes: “The system promotes a hierarchy and, as a result, aides look for ways to exert their own power to consolidate it for their bosses. This sometimes requires hush-hush dirty work and brutal machinations.” Among these suspicious figures was Michael Fawcett, a former assistant valet to Charles who climbed the ranks to become the prince’s senior valet.

In 2003, allegations surfaced suggesting that “Fawcett the Fence,” with the blessing of then-Prince Charles, had been involved in the sale of unwanted gifts from foreign dignitaries and had been allowed to keep a portion of the proceeds. An official inquiry ultimately cleared Fawcett of any criminal wrongdoing, but the incident cast a shadow over the situation.

Employing an aide who operated on the fringes of legality became untenable for Palace officials, prompting the institution to exert pressure for change. Despite King Charles’s reluctance, Fawcett eventually resigned from his role as the prince’s personal assistant.

Read: Prince Harry Spare review on NationalWorld News

Officially, Fawcett was no longer on the Palace’s payroll. However, within a matter of weeks, he established a new management company, Premier Mode, and the prince rehired him as a freelance consultant. The institution might have distanced itself from Fawcett, but Prince Charles remained deeply connected to him. The prince not only brought back his loyal aide as a hired expert, primarily in the capacity of a “party planner,” but in 2018, he appointed Fawcett as the chief executive.

In this role, Fawcett oversaw the entire operation of the Prince’s Foundation, personally leading numerous successful fundraising campaigns that generated substantial funds for the foundation’s diverse initiatives, including the renovation of the Dumfries House Estate and the provision of education and training programs in construction and traditional crafts. He resigned from The Prince’s Foundation after accusations he offered to help secure a knighthood for Saudi donor.

If these are the sources we are relying on for information, it may be necessary to assess the accuracy and reliability of the information we consider as truth.

On the other hand, for seventy years, the late Queen Elizabeth II’s actions are said to have constituted “a PR triumph of evasion,” and indeed, there were very few scandals in comparison to her son’s.

“While they are constantly evolving, the relationships between the press and the institution can be separated into three silos: the royal rota; sources, leaks, and briefings; and the darker world of interference, obstruction, and control.”

Similar to the White House press corps, the royal rota has been the official way for media to access taxpayer-funded royal engagements and activities for years. Scobie claims that the publication of Prince Harry’s memoir “Spare” highlighted how “almost every press officer and courtier has a hotline to the press.”

Read: Fact checking book: Endgame raises questions over other books

While many journalists covering the royal beat engage in what’s commonly known as royal “churnalism,” which involves recycling press releases, rephrasing details from royal rota reports, and echoing briefing notes provided by Palace aides, larger media organisations also prioritise generating their own news content. This includes pursuing exclusives, receiving leaks from undisclosed sources, and engaging in both on-the-record and off-the-record briefings, constituting the second category of interactions between the Palace and the press.

“Joined at the hip, two troubled institutions now require each other for relevance in a culture that, to a large degree, is moving on without them.”

Scobie does not see anything particularly wrong with off-the-record briefings and sources speaking anonymously – of course, this is common in journalism. However, there is something insidious about these sources using the media as a mouthpiece for their own agenda. It undermines the purpose of a free press if it refrains from scrutinising claims from such sources. While it is acceptable for publicists and representatives of celebrities, sports stars, politicians, businesses, and governments to use the ‘on background’ or “off the record” method, it appears somewhat questionable when it comes to a presumably divine power relying on these practices

Queen Camilla’s influence and shifting media relations

Queen Camilla’s alleged “mutually advantageous friendship” with Mail editor Geordie Greig and her ongoing association with the Mail’s publisher, Lord Rothermere, who holds a prominent position in the British media, has undoubtedly contributed to these developments, Scobie writes. As former BBC royal correspondent Peter Hunt noted, “Camilla has been canny,” adding “She’s kept the media close and the Daily Mail even closer.”

Scobie asserts that the dynamics between the monarchy and the British media have undergone a significant shift. Previously, the royal family relied on the print press as an ally in promoting their objectives. However, the situation has evolved to the point where the Palace has transformed into a source of content without a discernible overarching purpose. Instead, it is making strenuous efforts to generate enough material to sustain its fragile connection with the media. He writes: “Where once the royal family needed the print press as a partner for advancing their agenda, it is now in such dire straits that the Palace has mutated into a feeder machine.”

The Sussexes’ attempt at control

The Sussexes cannot be absolved of involvement in this situation either. They have previously engaged in similar questionable practices and appear to have suffered the consequences. In an attempt to avoid repeating their past experiences, the couple has embarked on establishing a three-part organisation consisting of the Archewell Foundation, Archewell Audio, and Archewell Productions.

A notable instance of their efforts to change the narrative occurred in January 2022 when they unexpectedly declared that “unnamed sources” would no longer represent their interests. They declared that only the official communications team at Archewell would be authorised to comment, or abstain from doing so, on any matters concerning them. While this move would have been commendable if successfully implemented (especially considering the prevalent use of anonymous briefings within the royal circle), it struck both the public and the media, including Scobie, as perplexing when, just a week later and thereafter, unnamed “sources” continued to speak on behalf of the couple.

Since that time, the couple has restructured their approach to media strategies and appointed a new head of communications, Ashley Hansen, a former executive at the Universal Film Entertainment Group. The issue of unclear guidelines regarding sources remains unaddressed by their team.

The verdict: freeing the media from the monarchy

In the end, this book makes the same mistakes as its subjects. Scobie talks about having interviewed 60 sources, an apparently more “leaner pool” than this his previous book on the Duke and Duchess of Sussex “Finding Freedom.” He says that there are benefits to having anonymous sources as it allows “the freedom to speak candidly and critically without fear.” The author states that a number of people also spoke “on background,” which means their quotes were not included in the book, and some also spoke strictly off the record.

And therein lies the rub. The nonfiction work is another reminder that when it comes to the royal family, the media should not be relying on salacious rumours and tittle-tattle. If the monarchy is genuinely meant to have a celestial mandate to govern, it is imperative that we elevate ourselves beyond sensational tabloid content and their malicious methods of operation. This elevation is essential to maintain a clear distinction between the affairs of the state and the principles of a free press. Then we can see if it truly is the “endgame” for the royal family.

[…] Several royal books, including Prince Harry’s bestselling memoir “Spare” and Omid Scobie’s “Endgame,” had their review features disabled due to users trashing the books without reading […]

[…] more is there are 22 books of the same nature, including Omid Scobie’s book “Endgame,” a summary of Timothy Ferriss’ work “The 4 Hour Body,” and much more. The […]