It’s Oscars season, and while viewers had their eyes on the red carpet, readers were looking at all of the successful book-to-film adaptations. From “Oppenheimer” to “Flowers of the Killer Moon,” one film that took the concept quite literally is “American Fiction,” starring the formidable Jeffrey Wright.

Warning: Spoilers ahead.

What book is American Fiction based on and what is it about?

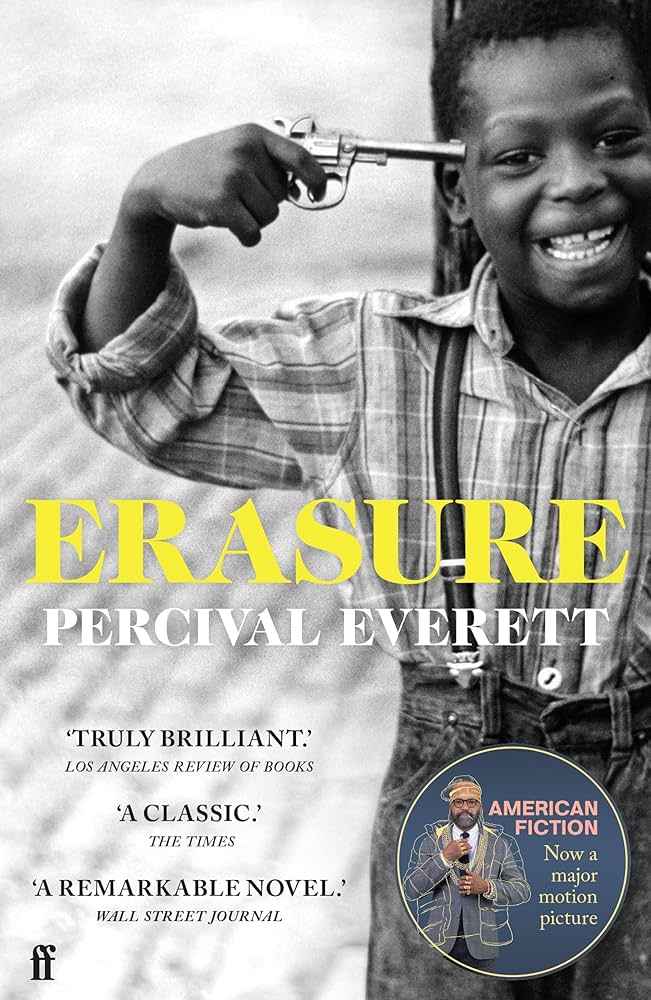

“American Fiction” is based on the 2001 novel “Erasure” by Pulitzer Prize finalist Percival Everett. This dark comedy follows a frustrated novelist and professor who writes an outlandish satire of stereotypical “Black” books, only for it to be mistaken by the liberal elite for serious literature and published to both high sales and critical praise.

The Hunger Games actor plays the protagonist Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, who is disillusioned and depressed for being constantly overlooked. He says: “They have a ‘Black’ book, I am Black and it’s my book.” Ironically, his name derives from two great Black artists – jazz piano virtuoso Thelonious Monk, and National Book Award winner Ralph Ellison. It showcases how the white establishment reduces Black bodies and in this case, true geniuses, into palatable bite-size pieces.

“My problem is that books like this aren’t real. They flatten our lives… These things reduce us and they do it over and over again because too many white people, and people apparently like you devour this slop like pigs at a dumpster to stay current at f**king cocktail parties or whatever.”

‘Monk’ in American Fiction

Soon after, he comes across a publisher-turned-author Sintara Golden, who has become incredibly successful from her work. She says: “Where’s our stories…it’s from that lack my book was born.” Unfortunately, what she produces is a type-casted version of an African American family called “We’s Lives in Da Ghetto.” Monk eventually calls her out on this kind of “pandering” to the liberal elite, which she cannot deny, but will not belittle either. But she also holds up a mirror, stating: “Do you get angry at Bret Easton Ellis or Charles Bukowski for writing about the downtrodden? Or is your ire strictly reserved for Black women?”

Read: Tupac Shakur biography: a life marked by struggle and death – review

On top of this, Monk suddenly loses his equally impressive sister, who had been caring for their increasingly frail mother. As a result, he becomes her guardian and essentially the patriarch of his family facing trying circumstances. It’s a perfect storm for ‘going off the rails,’ which is legitimate in Monk’s case. Like any microaggressions, it’s death by a thousand paper cuts.

His vitriol then turns toward the system that lauded the bestselling writer, Golden. His only solution is to follow the same path and suck up to the masses in a moment of deep-seated anger. “It’s got deadbeat dads, rappers, crack, and he gets killed by a cop in the end. I mean, that’s Black, right?… I just want to rub their noses in the horses**t they solicit,” he tells his agent, who is less than impressed.

Adopting the pseudonym Stagg R. Leigh, he is offered $750,000 as an advance for what he considers the most “lucrative” joke he has ever told. It’s no coincidence that he chose this name. “Stagger Lee” or “Lee Shelton” as he was also known, was an African-American pimp in the 19th century who was accused of murder. His transformation from Monk to ‘Stagg R. Leigh’ therefore symbolises how Black artists are diminished, stripped of their complexity and nuances. This is what Hanif Abdurraqib also describes in “A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance,” where he highlights the varied ways that “Blackness and Black performance is commodified and reshaped for American consumption.”

How Black creatives are reduced down to a commodity

Speaking to Brene Brown on her podcast in 2021, the critic and writer said, “I was writing a book about America’s response to Black performance through the lens of appropriation and through the lens of commodification, and through the lens of whiteness as a container for Black performance.”

Read: Jordan Peele: Out There Screaming is intersectional horror at its best – review

We’ve seen groundbreaking horror director Jordan Peele do something similar in “Get Out,” where Black bodies are literally objectified. Abdurraqib states “Jordan Peele has given us a decade of looking through the anxieties of belonging and not belonging. Of duality and shapeshifting. There was no logical way for this to end but with his horror obsession.” This dichotomy in character also appears in Monk, who transforms from being the responsible adult to pretending to be someone completely opposite.

His agent explains that people want “easy” reads, comparing the premium Blue Jack Daniel label to the Red version. He tells Monk: “Now, for the first time ever, you’ve written a Red book. It’s simple, prurient. It’s not great literature, but… satisfies an urge. And that’s valuable.” Monk is repulsed by the idea but feels completely defeated, so he pushes the analogy as far as possible. He claims to be a wanted fugitive to indulge the clueless editors, fully aware that no one would conduct any fact-checking because they are underpaid. It illustrates the bizarre gatekeeping of the publishing industry, in which some identities are more valued than others. Hence we end up with a form of homogeneity, instead of allowing a much more florid landscape.

Read: Black British History: UK adults lack knowledge, new study finds

Moreover, it starts to showcase the duality of being a Black creative. On the one hand, he detests the commercial aspect of the industry that only accepts one kind of voice, while at the same time, becoming the thing that he hates. Inevitably, he tortures himself, knowing that the book is mediocre and the only thing the publishing industry would accept.

“The dumber I behave, the richer I get.”

‘Monk’ in American Fiction

As mentioned in a previous Friday opinion piece about the lack of diversity in the industry, both R. F. Kuang and Zakiya Dalila Harris bring these ideas to the fore in their respective books “Yellowface” and “The Other Black Girl.” “Yellowface” is a meta novel, which looks at how Asian-American narratives are stifled within publishing due to white privilege. Similarly, Harris’ book scrutinises the lack of inclusion even on the other side of the process. Both are stark in their depictions, showcasing how DEI initiatives are tick-box exercises, that only welcome a certain type of person that can fit in within a small bracket.

Read: Women of colour still underrepresented in publishing

Of course, this means that they want to release Monk’s book on Juneteenth, not before he suggests changing the name from “My Pafology” to “F**k” as a joke. The whole situation is so ludicrous that it feels like an out-of-body experience, which he actually has at one point while writing these ridiculous characters.

The flattening of culture

Monk is outraged when he finds his girlfriend reading said book. For him, there is no glory in writing a book that serves only the purpose of commodification. He says: “My problem is that books like this aren’t real. They flatten our lives… These things reduce us and they do it over and over again because too many white people, and people apparently like you devour this slop like pigs at a dumpster to stay current at f**king cocktail parties or whatever.”

It is almost predictable what comes next: all the accolades for this book and white industry officials fawning over the rawness and realness of it all.

“American Fiction” is a far tamer version than the book, which was hugely experimental, bringing together various narratives, personal letters, story ideas, and imagined dialogue between his characters—essentially, Monk’s writing braindump. With the film, we are outside looking into the situation. Hence, we perceive these racist tropes with a similar external lens, instead of examining the tropes themselves. Consequently, we only get a tiny glimpse of the big picture of racial challenges within the publishing industry. “Erasure” is all about losing yourself to these market forces, which in a way, Monk does in the end.