“The flat place is the place of grief, but also the place of the real”, writes Noreen Masud in her debut memoir “A Flat Place.” The Pakistani-born writer has been hailed for her visceral work, picking up nominations for the Women’s Prize, the Jhalak Prize, the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, and the RSL Ondaatje Prize. For Masud, the rawness of flat landscapes is not just a physical preference but a profound psychological mirror that reflects and validates her complex emotional landscape shaped by Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (cPTSD).

“Landscapes are the sites of so much pain, and flatlands are no exception; pain’s been compacted and trodden into them over hundreds of years.”

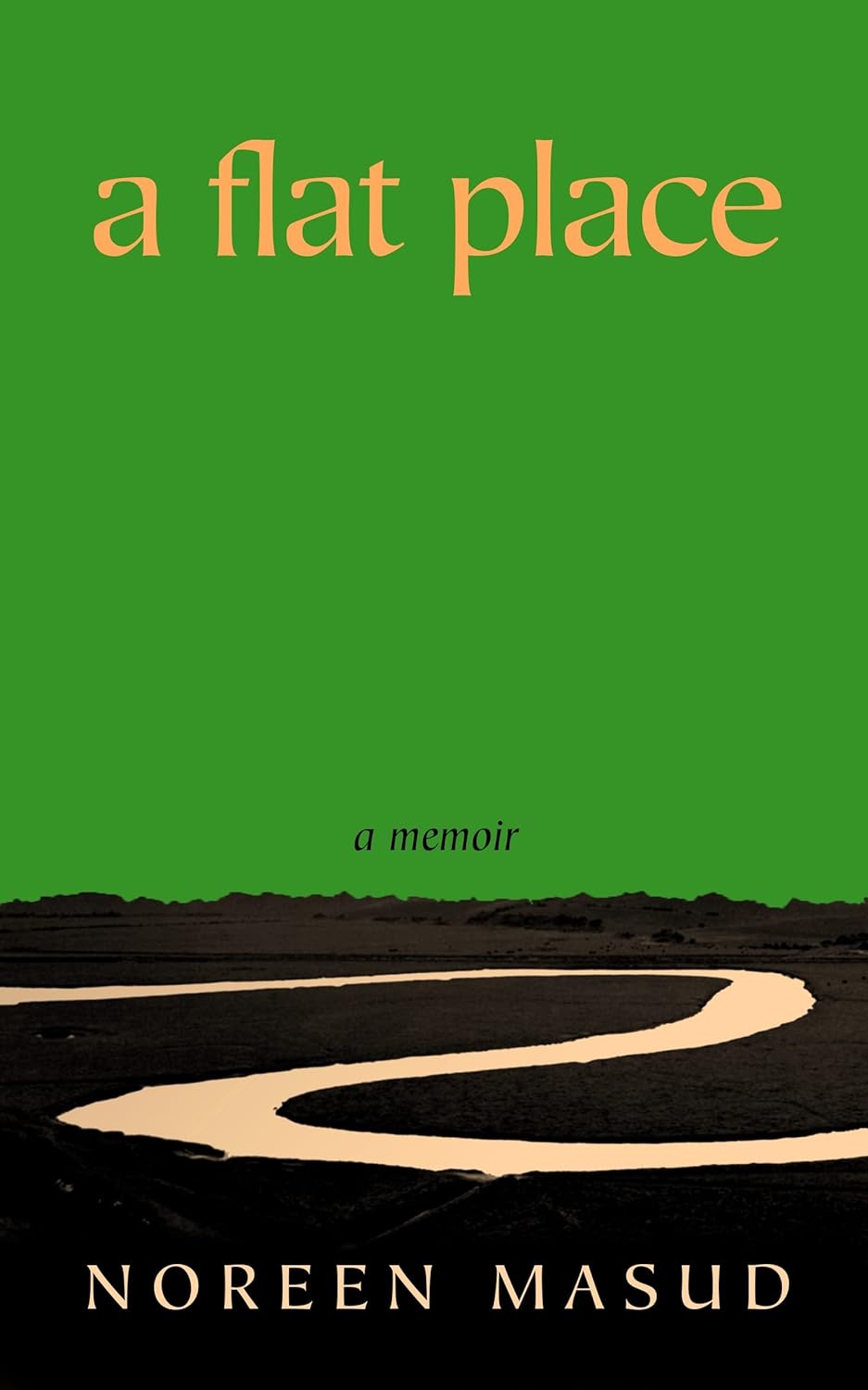

Who is ‘A Flat Place’ author Noreen Masud?

MEET THE AUTHOR

Noreen Masud

Noreen Masud is a British author and academic.

Born in Lahore, Pakistan to a British mother and Pakistani father, she relocated to Britain as a teenager along with her mother and siblings.

Masud teaches at the University of Bristol and has contributed to publications such as The Times Literary Supplement and Salon. Her scholarly work, “Stevie Smith and the Aphorism: Hard Language” (2022), earned the Modernist Studies Association’s First Book Prize.

She has also appeared on BBC Radio 4’s “In Our Time”.

Her memoir, “A Flat Place: Moving Through Empty Landscapes, Naming Complex Trauma” (2023), recounts her upbringing in Pakistan, her move to Scotland at age 15, and her struggles with complex post-traumatic stress disorder. The memoir was named a Book of the Year by The New Yorker, The Guardian, and the Sunday Times, and was shortlisted for the 2023 Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year Award and the 2024 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction.

The paradox of flat landscapes: stiff, still, and deeply personal

The book is personal to me as a fellow cPTSD sufferer, aware of the lack of understanding around the condition. That being said, Masud is clear about stating that her work is not meant to be “a narrative about complex post-traumatic stress disorder”, given how personal it is to each individual. In the ‘Note’ section of the work, she clarifies: “It was, solely, a study of encounters with flat landscapes. It was in writing it, and in discussion with my agent, that I came to understand that the complex trauma I sustained in my early life was an element which could not be omitted.”

“I speak only for myself in this book, out of one (remarkable and precious) therapeutic relationship, which has only ever legitimized my anger about racial and economic injustice, rather than trying to anaesthetize it, and which seeks to support me to reenter the collective (whatever that may be) in my own ways and on survivable terms.”

What she finds is the multi-dimensional aspect of both flat places and trauma. Flat landscapes, with their unvaried and featureless expanses, symbolise the emotional flatness or numbness often experienced by people with cPTSD. It is a characteristic response where emotions are suppressed, and life feels distant and unreal. Her relationship with flat landscapes, like her emotional state, is “stiff and still,” showing no compromise or variation (unlike more dynamic or picturesque landscapes).

Listen: Why children should learn the truth – Stolen History author Sathnam Sanghera

She notes, “Perhaps we love the things that reflect our own delusions about ourselves back to us. I love stones because they are old and hard and sure, which is how I feel, even though I am not. I love flat landscapes for much the same reason. They won’t compromise. They are stiff and still, like me.”

The psychoanalyst Robert Stolorow argues that trauma stems from the disruption or loss of connections to others. He suggests that cPTSD can arise when one lacks secure, responsive attachments. This occurs either when attachment figures do not shield one from the ‘terrors of the world’ or, more commonly, when these figures themselves are the source of fear. Consequently, from infancy, the person fails to perceive others as safe havens or to form stable emotional attachments.

Historical and cultural roots of trauma

The book also discusses the experience of derealisation, a dissociative symptom of cPTSD where the world seems surreal or distant. Flat landscapes articulate her experience of the world as disconnected and two-dimensional, showcasing a loss of depth in both perception and emotional experience: “When I derealize, the world becomes distant and two-dimensional: a ribbon of time, where all moments exist at once, with colours, and shapes, and mouths opening and closing harmlessly.”

Masud describes this stemming from her difficult and ungraspable personal history of neglect and control by her father while living in Pakistan. As she notes: “Relationships are one of the most challenging aspects of complex PTSD. They’re both the source of terror and the cure for that terror.” However, it’s important to recognise that the book does not pit different cultures against each other. Instead, it highlights how trauma is shaped in each place and how external influences such as colonialism and ignorance can reshape or exacerbate mental health issues.

Read: Partition of India: best books to understand independence

Linking the instability of land with the instability of identity, she writes, “In 1947, four Muslim-majority areas in the West of India—West Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, and the North-West Frontier Province—joined with East Bengal, 1,500 kilometers away, to become Pakistan, at the same time as the rest of India gained independence from the British. But immediately the country was faced with the question: What did it actually mean to be Pakistani? What, in practice, is a ‘Muslim homeland’?” This uncertainty has created a persistent identity crisis that plagues the nation and its people.

Masud contemplates her disconnection, stating, “It was no wonder, really, that I had no sense of how to connect with other people. Stuck in its own postcolonial drift, Pakistan had never been able to work out, either, what it meant to belong.” She links the country’s turbulent political landscape directly with her feelings of alienation—an existential query that haunts postcolonial societies.

Listen: How the body is political – with Shame on Me author Tessa McWatt

Looking further into the dichotomy between Western perceptions and Eastern realities, Masud critiques the double standards in how trauma and hardship are perceived globally. During the pandemic, the University of Bristol lecturer observes, “It wasn’t until the pandemic that I realized this was a racist double standard… While I was breathing easier for the first time in years, everyone around me was going mad.” She criticises the Western lens on non-Western suffering and challenges the reader to reconsider what constitutes trauma and resilience.

As a researcher, she explored the concept of the “human zoo” in Newcastle, a topic that more writers have recently engaged with. When we spoke with “Shame on Me” author Tessa McWatt, she also mentioned this notorious part of British history, in which Saartjie Baartman, a Khoikhoi woman, was exhibited as a freak show attraction in 19th-century Europe under the name Hottentot Venus. She realised that “People of colour have always been here, in Britain’s flat places, living and struggling. Violence and oppression form the bedrock of the landscape that I recognize and move through.”

“The fens were drained at great effort and expense; the smooth green landscape they left behind is kept that way with high walls, regular inspections, dredging of canals. Nature and culture intertwine indissolubly in the fenlands, as in every person.”

The flat landscapes metaphorically represent the erasure of history and personal trauma, much like the draining of the fens removed the natural history and biodiversity. Masud talks about feelings of being detached from her past and the historical erasure of trauma experienced by her community.

Resilience and stability in uniformity

For Masud, she describes feeling detached and disassociated, comparable to the unchanging, indifferent nature of the flat terrain. She writes: “On the top is thick joy, moving around like the sea, full of fish and slopping goofily at the edges… The bottom layer is the cold sea floor, where insects pick through dead things. I’m in the top layer, and then suddenly I’m tired and I’m back on the floor, my cheek against the whisper that says nothing matters. There’s no space in between.” This emotional state mirrors the geographical flatness—both lacking significant variations or points of interest that might otherwise evoke a strong emotional response.

She also appreciates the flat landscapes for their steadfastness and resistance to change, similar to her own emotional state which refuses to surrender under the pressure of conventional social interactions and emotional exchanges. While visiting a small English town near Ely, she was confronted with Union Jack flags on several residences. The act for her seemed like “the country seemed unsure of itself” as its “identity had to be enforced” onto a place which kept shifting and turning. She adds: “People tried to brand it with anxious bits of national tat. But in the end they just disintegrated or fluttered away, leaving the place alone, itself, unchanged.” In a world that feels overwhelmingly unpredictable and unsafe, the unchanging horizon of a flat landscape provides a visual anchor of stability.

Read the review: Hannah Durkin: the Clotilda slave survivors and its lasting legacy

Hence “A Flat Place” by Noreen Masud illustrates her multifaceted connection to flat landscapes —serving not only as a reflection of her emotional numbness and derealisation but also as a symbol of the enduring, unchangeable impact of her traumatic past. It’s an external representation of her internal reality, where the lack of significant landmarks or features in the landscape parallels her difficulty in identifying specific, singular traumatic events that have shaped her. The expansive areas are punctuated by roots and submerged forests that she occasionally stumbles over, much like her childhood memories. Her trauma is prolonged and diffuse, like the endless flat horizons she describes.

How To Be Books is part of The Heritage Reads Book Club, chosen as one of six book groups by the Women’s Prize and The Reading Agency to read their nonfiction shortlist. ‘A Flat Place’ by Noreen Masud was the club’s designated read.

[…] withdrawals include writers Noreen Masud and AK Blakemore, climate activist Tori Tsui, and comedian Ania Magliano. Blakemore expressed […]

[…] a recent event hosted by the Heritage Reads Book Club alongside How To Be Books, Noreen Masud shared her insights from her celebrated non-fiction work, “A Flat Place.” Masud’s […]