I must confess that I have conflicting emotions regarding Martin Scorsese’s adaptation of “Killers of the Flower Moon.” Despite its critical acclaim for capturing David Grann’s masterful book from 2017, watching the film through the lens of Hollywood’s white perspective is unsettling. Regrettably, it fails to escape its own biases, humanising genocidal murderers while diminishing the agency of First Nations.

Is Killers of the Flower Moon based a true story?

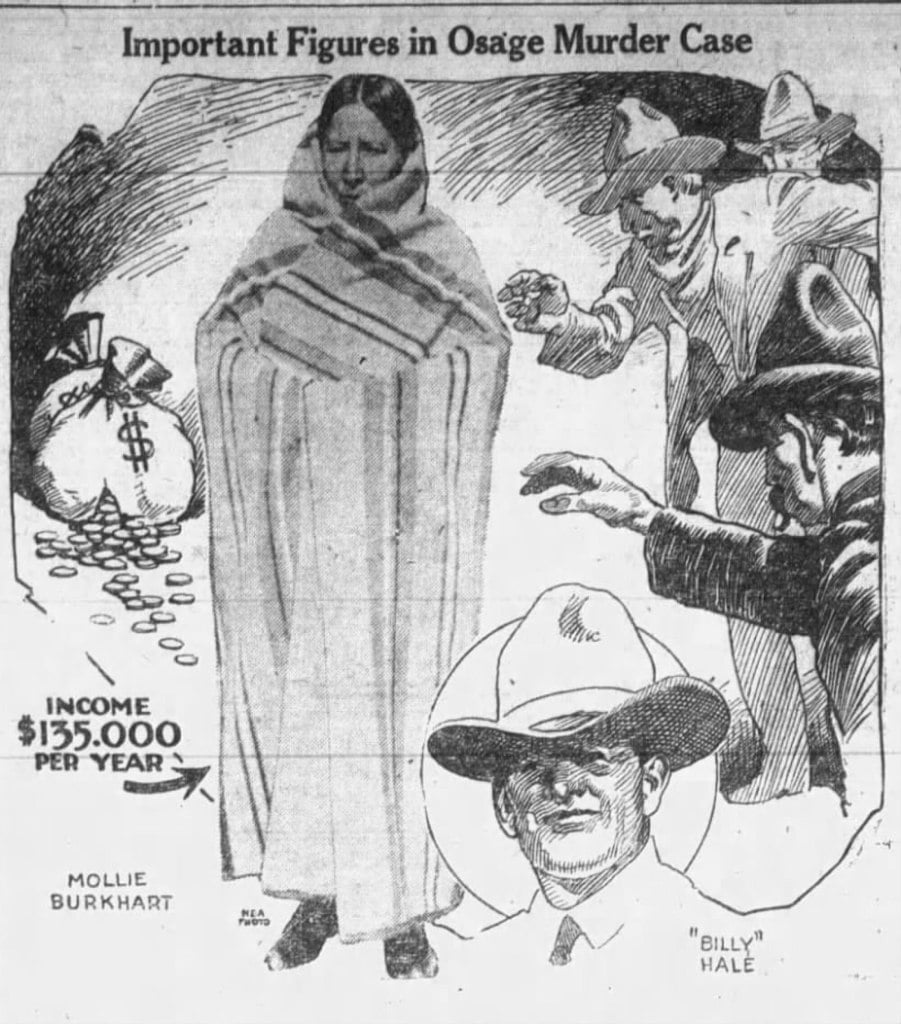

The movie boasts a star-studded cast, featuring Oscar winners Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert DeNiro, and Brendan Fraser playing questionable characters. It recounts the harrowing true story of a series of brutal murders in the 1920s targeting members of the Osage Nation on their Oklahoma land. Central to this narrative is Mollie Kyle, whose family was systematically killed.

Grann explains in the book that in the early 1870s, “the Osage had been driven from their lands in Kansas onto a rocky, presumably worthless reservation in northeastern Oklahoma, only to discover, decades later, that this land was sitting above some of the largest oil deposits in the United States.”

Read: The Wager by David Grann on ‘the mutiny that never was’ – review

This “black gold” led to members becoming some of the wealthiest per capita in the world at the time. The journalist says that in 1923, with roughly 2,000 people on the tribal rolls, the group “collectively got more than $30 million (in payments from oil companies leasing their land),” which translates to about $400 million in today’s dollars. And while “few Americans owned a car at that time, many Osage had numerous cars, as well as many servants, often white.” Prospectors had to pay royalties and leases to the Osage to access the oil.

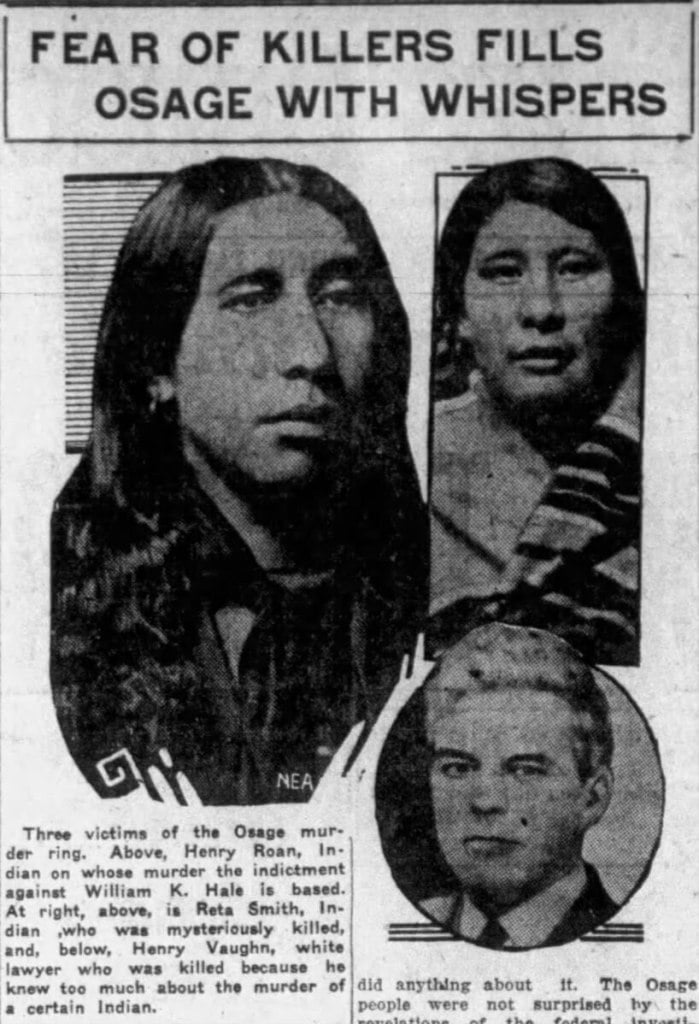

Tragically, from 1918 to 1931, more than sixty wealthy, full-blood Osage Natives were murdered in an attempt to steal their “headrights.” These headrights, essential for controlling the mineral trust, could not be bought or sold but only inherited. Mollie and her family were among the first victims of this underground reservation.

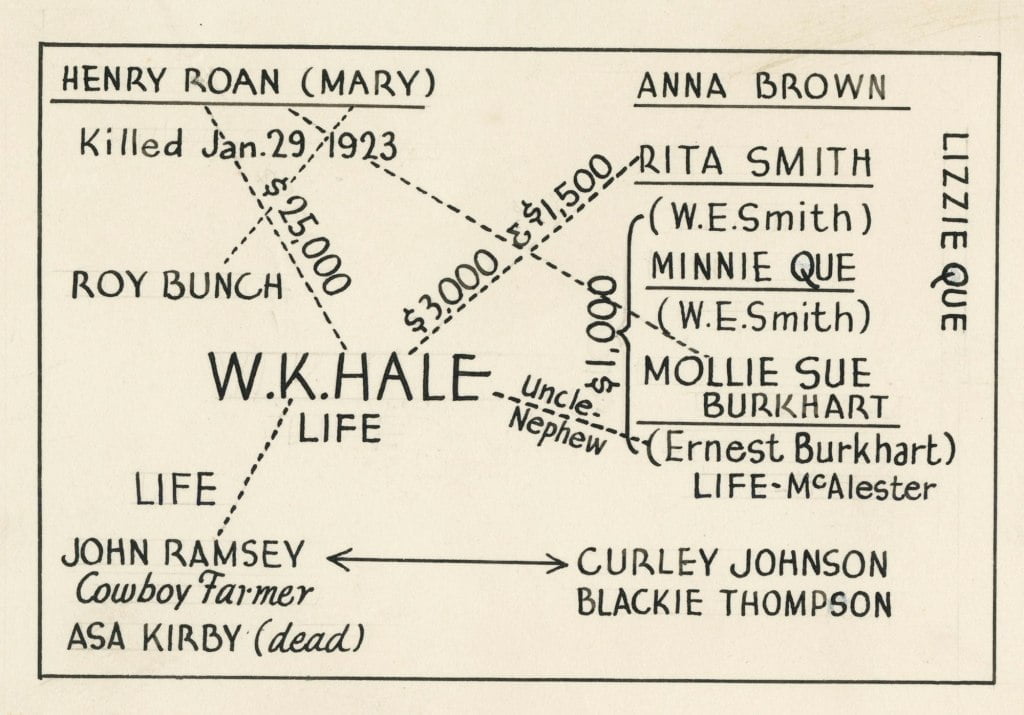

William King Hale, a political and crime boss in Osage County, suggested that his nephew Ernest Burkhart marry Mollie to seize her fortune. The film portrays the brutal killings of her siblings and relatives, along with her own decline in health due to her husband’s slow poisoning. It’s a sombre and horrifying chapter in history, highlighting the grave mistreatment of Indigenous communities even within the last century.

What does ‘killers of the flower moon’ mean?

The Old Farmer’s Almanac, which initiated the practice of publishing names for the full moons in the 1930s, documented the name bestowed upon the May full moon by American tribes as the “Flower Moon.” This name originated from the abundance of flowers blooming across North America during May, symbolising the arrival of spring after a harsh, cold winter.

However, during this period in the Oklahoma hills, the flourishing flowers met their demise as taller plants overtook them, prompting the Osage to dub that month as the “time of the flower-killing moon.” The tragic murder of Anna Brown, Mollie’s sister, occurred in May 1921, making the title serve as a poignant metaphor for the harrowing events that unfolded within the Osage community.

Why is the film seen as controversial?

The film’s own Osage tribe consultants have actually criticised the movie. Christopher Cote, an Osage language consultant for the film, spoke at the LA premiere, saying he had been “nervous about the release of the film,” and now that he’s seen it he had “some strong opinions.”

The history of the murders, he said, “is being told almost from the perspective of Ernest Burkhart and they kind of give him this conscience and kind of depict that there’s love.

“But when somebody conspires to murder your entire family, that’s not love. That’s not love, that’s just beyond abuse.”

“As an Osage, I really wanted this to be from the perspective of Mollie and what her family experienced, but I think it would take an Osage to do that.”

Christopher COTE

He added: “As an Osage, I really wanted this to be from the perspective of Mollie and what her family experienced, but I think it would take an Osage to do that.” And this is noticeable. Lily Gladstone, who plays Mollie, is not only voiceless in the film, it gives her absolutely no real role in her own victimisation. She is a body that these heinous crimes are happening to.

Cote also highlighted that he thinks Scorsese did “a great job representing out people,” but the movie “isn’t made for an Osage audience.” Fellow Osage consultant, Janis Carpenter said she too had “mixed feelings”, stating: “Some things were so interesting to see, and we have so many of our tribal people that are in the movie that it’s wonderful to see them. But then there are some things that were pretty hard to take.”

How Mollie is different from the film

The book itself, showcases the story in a completely different way, documenting Mollie’s power in seeking justice, and from the perspective of the FBI inquiry. It certainly did not depict her homicidal husband as some kind of white saviour. Grann relays Mollie’s fight for her life in a passage that says: “in late 1925, the local priest received a secret message from Mollie. Her life, she said, was in danger. An agent from the Office of Indian Affairs soon picked up another report: Mollie wasn’t dying of diabetes at all; she, too, was being poisoned.”

Here we see Mollie taking an active role in trying to stave off death, in contrast to the film adaptation where she spends much of her time bedridden, writhing in pain – although this was sadly part of it. The book adopts a true crime narrative, meticulously documenting events through investigations and local archives.

“[In] late 1925, the local priest received a secret message from Mollie. Her life, she said, was in danger.”

David Grann, from “Killers of the Flower Moon”

Scorsese, known for his films about organised crime such as “The Departed” and “The Irishman,” uses his interest in this genre to frame the story. However, this approach sometimes detracts from the core horror of the situation. He attempts to rectify this with a surreal dreamlike montage at the film’s conclusion. Instead of traditional post-credits information, he presents it as an age-old live true crime radio show, commissioned by then-FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. In an unexpected twist, Scorsese reads Mollie Kyle’s obituary, revealing her tragic death at the young age of 37, with the murders never officially recorded.

Ongoing challenges faced by Native American reservations

He rightly stresses the lack of justice faced by First Nations people. For instance, Native Americans experience a poverty rate twice the national average, and their impoverished living conditions and limited access to medical resources contributed to a significantly higher COVID-19 infection rate, which was 3.5 times that of white Americans. However, the plight of Native Americans has often been callously overlooked.

Before shooting, Scorsese however, said he realised the movie focused too much on white men. “After a certain point, I realized I was making a movie about all the white guys,” Scorsese told Time. “Meaning I was taking the approach from the outside in, which concerned me.”

The script underwent a significant overhaul, shifting the dramatic focus away from FBI investigator Tom White’s inquiry to spotlight the Osage and the circumstances that led to their systematic killings without consequences. Interestingly, DiCaprio was originally slated to portray this character prior to the changes, while Jesse Plemons ultimately took on the supporting role of White. Despite receiving praise from a descendant of one of the Osage murder victims, it’s challenging to overlook the transition from one white-centred narrative to another.

Environmental concerns and the Mancos-Gallup Amendment

Even in the present day, the lands of the Navajo and Puebloan in northwestern New Mexico, where Counselor is located, continue to witness drilling activities. The region saw its first oil well drilled in 1911, with natural gas exploration following shortly thereafter.

“For cultural resources in the path of the unconventional oil and gas trajectory, like those of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, these trends will result in permanent cultural losses.”

Hillary M. Hoffmann, “Fracking the Sacred” in the Denver Law Review

Today, the US Bureau of Land Management is contemplating the Mancos-Gallup Amendment, a plan that could authorise the leasing of land in the area for around 3,000 new wells, many of which would be used for fracking oil and gas extraction. This proposal threatens to expand drilling into some of northern New Mexico’s last remaining public lands, posing risks to the desecration of sacred Native artifacts near Chaco Canyon and exacerbating existing public health challenges in an area that has already been severely affected by one of the world’s worst COVID-19 outbreaks.

Hence in “Killers of the Flower Moon,” Grann quotes members of the Osage Nation saying “There were a lot more murders during [this] Reign of Terror than people know about. A lot more.” And sadly, despite being 100 years since the murders, we are still seeing this suppression across Native American reservations. In this way, the film regrettably fails to adequately highlight this persistent contemporary issue, and could have made a more significant impact if Scorsese had provided a platform for someone from the Osage community to voice their perspective.

[…] Read: Killers of the Flower Moon: book outshines Scorsese film – review […]

[…] were looking at all of the successful book-to-film adaptations. From “Oppenheimer” to “Flowers of the Killer Moon,” one film that took the concept quite literally is “American Fiction,” starring the […]