It was once said, “History is written through a rear-view mirror but unfolds through a foggy windshield,” regardless of the proximity. In this case, Dr. Hannah Durkin examines the last known US slave ship, the Clotilda, which arrived in Mobile Bay in the late 1850s, carrying 110 African men, women, and children from Africa to the United States.

When people think of the 19th century, many feel there is sufficient distance for us to have made mistakes and already atoned for our sins. However, considering that Oxford University is older than the Aztecs and existed hundreds of years before the Clotilda, it puts things into perspective. Just imagine that the last ship carrying slaves sailed during the period when Charles Dickens wrote “Great Expectations” and when the British Open was played for the first time.

Who is Dr. Hannah Durkin?

MEET THE AUTHOR

Hannah Durkin

Dr Hannah Durkin is a historian specialising in transatlantic slavery and African diasporic art and culture. She holds a Ph. D. in American Studies from the University of Nottingham and a Postgraduate Diploma in Journalism from Leeds Trinity University.

She has taught at Nottingham and Newcastle universities and recently served as a Guest Researcher at Linnaeus University in Sweden. The academic is also an advisor to the History Museum of Mobile, which is working to memorialise the Clotilda survivors, and was the keynote speaker at Africatown’s 2021 Spirit of Our Ancestors Festival founded by the Clotilda Descendants Association. She is the recipient of more than a dozen academic prizes, including a prestigious Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship.

Unveiling the legacy of the Clotilda

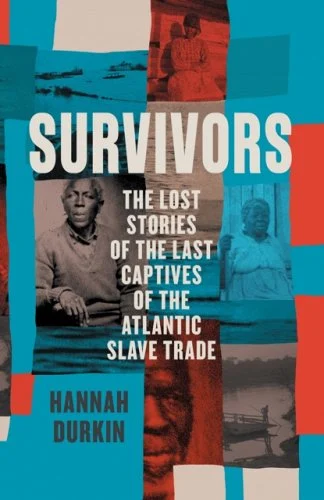

Durkin carefully researches the lasting legacy of the Clotilda’s slaves in her book “Survivors: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the Atlantic Slave Trade.” The book follows their lives from their kidnappings in what is modern-day Nigeria through a terrifying 45-day journey across the Middle Passage. It describes the subsequent sale of the ship’s 103 surviving children and young people into slavery across Alabama up to the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement in Selma.

However, it also highlights the establishment of an all-Black African Town (later Africatown) in Northern Mobile—an inspiration for Harlem Renaissance writers, including Zora Neale Hurston—and the founding of the quilting community of Gee’s Bend, a Black artistic circle whose cultural influence is enormous.

Read: Martin Luther King Jr book: Jonathan Eig humanises man behind pulpit – review

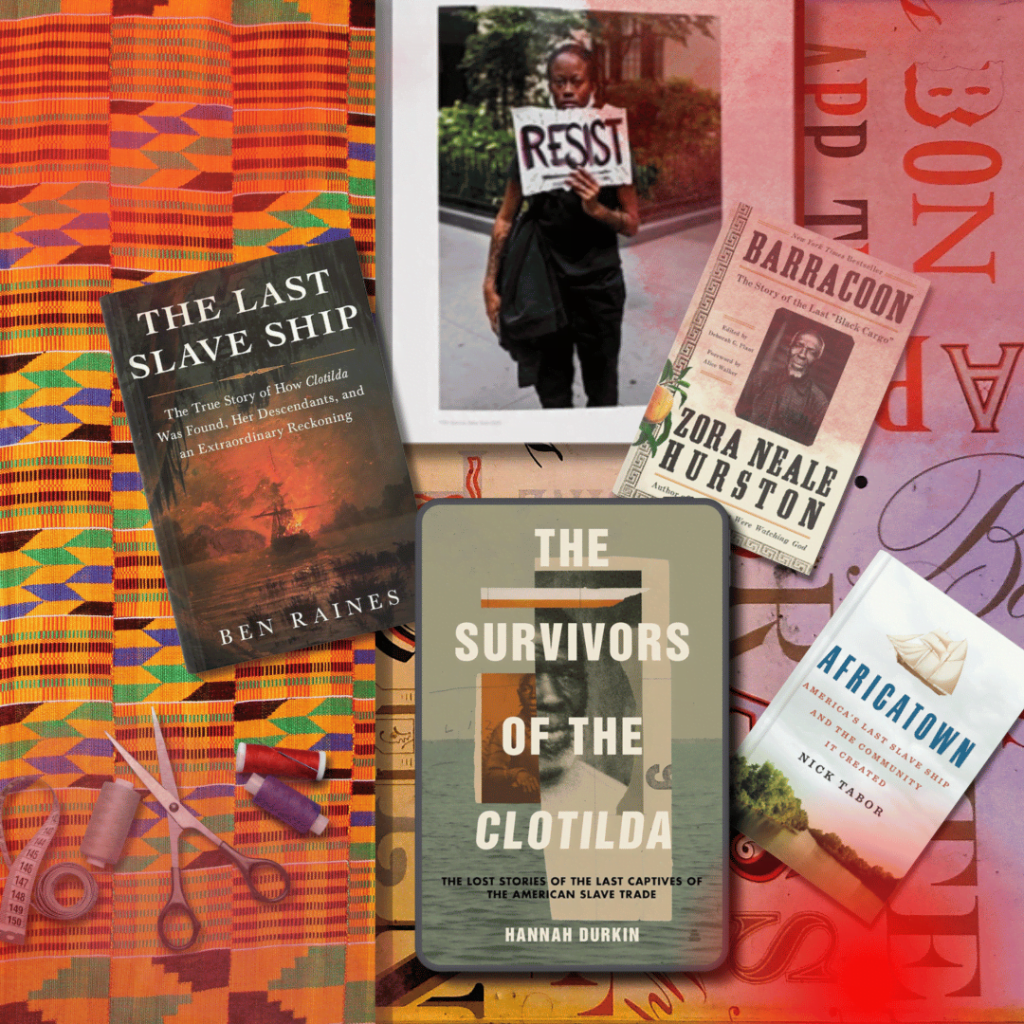

While there have been a number of books about this particular situation, as seen with Ben Raines’ 2022 publication “The Last Slave Ship: The True Story of How Clotilda Was Found, Her Descendants, and an Extraordinary Reckoning,” Durkin’s work focuses on the subsequent lives of the survivors. It’s hardly surprising that there’s been renewed interest in this period of history, given Hurston’s extraordinary account “Barracoon” was finally published in 2018.

Hurston was one of several reporters, anthropologists, and academics, who interviewed, among other survivors, Kossula, known generally as Cudjo Lewis. He remained alive until 1935 and was a valuable source of first-hand knowledge.

She investigated the lives of as many of the Clotilda’s 103 survivors as possible, with seven horrifically dying at sea, in what is described as the “middle passage”. Durkin delves deep into the history of the Clotilda captives, tracing their origins back to the Yoruba heartlands, a region now encompassing parts of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo.

“This trade in human life fuelled demographic breakdown and social instability, which in turn created military states compelled to engage in warfare instead of agriculture and trade prisoners for weapons to protect against their own people’s transatlantic enslavement by foreigners.”

Dr Hannah Durkin, ‘Survivors’

Using Hurston’s book as a starting point, she recounts the tale of Kossula, who vividly remembered his hometown Tarkar, erased from history during the brutal incursions of the Fon warriors. Durkin states the catastrophic impact of the slave trade on African societies “fuelled demographic breakdown and social instability” in the region. Kossula’s reflections shared only two years before he died in 1935, offer a troubling window into a world that once was, revealing his connections to significant Yoruba cities and his heartbreaking abduction.

The journey from Africa to Alabama

The author discusses the displacement of 10.7 million Africans, with 1.8 million dying during the Atlantic crossing and millions more perishing in raids and captivity, leading to only a seven-year life expectancy for slaves in the Americas.

Durkin’s work recounts both past atrocities, as well as the pervasive impacts of the slave trade on African societies. She communicates the cruel cycle of warfare and enslavement fuelled by European demand for labour, encapsulating the horrific toll it took on the African continent, including the immeasurable suffering endured by those who survived the journey only to face the brutal realities of enslavement in the Americas.

Read: The Wager by David Grann on ‘the mutiny that never was’ – review

The book also sheds light on the international efforts to end the slave trade, as well as the ineffectiveness of bans that were either ignored or inadequately enforced. Durkin exposes the reality that the transatlantic slave trade persisted long after its official end, with illegal trafficking continuing to devastate lives well into the 19th century.

“The year 1867 is widely accepted in the English-speaking world as the one in which the transatlantic slave trade ended. But there is compelling evidence that trafficking continued into the next decade, and with US involvement.”

Dr Hannah Durkin, ‘Survivors’

She then details incidents where slave ships, including an American ship, landed in Cuba well into the 1870s, contrary to official narratives. These accounts are substantiated by various historical figures and sources, including the explorer Sir Henry Morton Stanley and Cuban historian Perez de la Riva. Durkin quotes a British politician’s scepticism about Spain’s enforcement of the ban, illustrating the ongoing illicit trade: “he ‘did not attach implicit credit to the assurances of the Spanish Government that there had been no importation of slaves into Cuba of late years’”. It reiterates the persistence of slavery, while also implicating the global complicity extending far beyond the official abolition dates. She invites readers to reconsider the historical timeline and how pervasive it was.

The 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act had a pivotal role in intensifying the national debate over slavery, indicating its contribution to the violent conflict known as ‘Bleeding Kansas’. Durkin spells out how this legislation, which allowed settlers to decide on the legality of slavery in Kansas and Nebraska, became a flashpoint, exacerbating sectional tensions. She then goes on to show the economic motives driving the pro-slavery faction, stating, “Slave trade advocates argued that the South’s economy was at threat; unlike the North, which produced 90 percent of the nation’s manufacturing output… the South… was being starved of cheap foreign agricultural labour that would increase the region’s productivity.”

Read: A Fever in the Heartland: cautionary tale of the KKK’s invisible hoods – review

Economic, political, and environmental factors stoked the expansionist agenda of the slave-holding South, bringing attention to the contentious issue of importing more enslaved individuals to strengthen the South’s agricultural economy and political power, despite the serious ethical and humanitarian implications. Durkin showcases the context in which this occurred, especially as the nation was heading toward civil war.

Perhaps most moving is the narrative of personal histories, like that of Dinah Miller, whose harrowing experiences of child sexual exploitation and resilience offer a deeply personal perspective on the legacy of slavery.

Durkin also describes the journey of Jackson, who represents the broader experience of African Americans seeking a return to their ancestral homeland. She explains: “He knew the journey would be frightening… It would be a difficult journey.” The contrast between the harrowing past and the hopeful future is striking, as the Monrovia ship, despite its eerie resemblance to the slave ship Wanderer, becomes a vessel of liberation for Jackson.

Upon arriving in Monrovia, Liberia, Jackson is quoted saying: “You will please remember that we are not worrying over the thoughts of a civil rights bill, or any other bill. But we are in our own free country, where we have all the benefits of law and citizenship.”

On the other side of the world, “Despite Klan violence, Black men in the Black Belt continued to turn out in large numbers to vote in the years after emancipation.” This period saw the election of African American legislators, such as Benjamin Sterling Turner, James Thomas Rapier, and Jeremiah Haralson, to the US Congress, representing a significant, albeit brief, advance in Black political empowerment.

Read: A Few Days Full of Trouble: truth about Emmett Till murder will set us free – review

However, Durkin points out the era’s systemic racism, stating, “The voting system was now rigged against Black people in Alabama.” It’s a grim picture of the regression in civil rights, followed by the resurgence of white supremacy and the onset of lynching, with the first documented incidents in Dallas County. Henry Ivy was one of the victims of this ongoing massacre.

Does Africatown Alabama still exist?

By 1912, she notes, “African Town’s population grew to approximately two to three thousand,” a rather remarkable achievement for its residents. They established over a dozen stores, owned homes, and worked at the Sheip Lumber Company, as well as showed initiative by raising funds for education, demonstrating a strong commitment to community and future generations. However, it did not stop child captives like Cilucangy wanting to desperately return to her homeland. She said she wanted “to go back to Africa soon as I can get off to go.”

Dinah emerged as an important figure in the evolution of a distinctive quilting tradition and the cultural legacy of Gee’s Bend. The artistic hub recognised for its unique quilts reflected a deep connection to West African textile traditions. Durkin explains, “Historians have suggested that African American patchwork quilts generally, and Gee’s Bend quilts specifically, may have been influenced by strip weaving,” linking the quilts to a broader heritage that goes beyond the Atlantic experience.

She cites a federal government pamphlet from 1939, noting, “Even today some of the older people can speak a language that outsiders cannot understand – probably an African dialect,” which marks the far-reaching impact of the survivors’ African roots on the community. The reference to Gee’s Bend as an ‘Alabama Africa’ by minister Renwick Carlisle Kennedy epitomises the fusion of African and American identities.

Echoes of the past: Where is the Clotilda ship now?

Just north of downtown Mobile, in the muddy banks of the Mobile River, lies the wreckage of the schooner Clotilda. The remains were found on May 22, 2019, according to the Alabama Historical Commission.

“The Clotilda shipmates’ individual voices and stories therefore serve as a necessary corrective to dominant histories of transatlantic slavery that have framed personal horrors, traumas, griefs and the battle to adapt and survive in terms of numbers and statistics.”

Dr Hannah Durkin, ‘Survivors’

The Clotilda story is more than just about Alabama. It is a fragment of a wider story about transatlantic slavery, and these 110 captives represent a fraction of the 12.5 million people involved. Their experience of bondage and freedom, as well as their unusual landing in the US, contrasts with the broader history of the Middle Passage given so many others did not make it to the end. Despite the scars of their ordeal, the Clotilda survivors were able to preserve their African heritage, whilst also influencing significant civil rights milestones.

Thanks to their actions, historic moments such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a crucial early event in the civil rights movement, and the Selma Voting Rights campaign, led directly to the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Traces of their presence can still be found throughout Alabama, and their legacy, and their descendants, remain across the United States.

[…] Survivors: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the American Slave Trade by Hannah Durkin (January 18). This is an immersive and enlightening account of the survivors of the Clotilda, the final vessel involved in the Atlantic slave trade, whose life journeys intertwined and diverged in profound and meaningful ways. Read about the lasting legacy of the Clotilda in our review. […]

[…] Read: Hannah Durkin: the Clotilda slave survivors and its lasting legacy – review […]

[…] It was great to see Dr. Hannah Durkin in person, speaking about her new book “Survivors: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the Atlantic Slave Trade,” which we reviewed this year. Dr. Durkin shone a light on the histories of the Clotilda captives, the last group to be illegally shipped across the Atlantic into slavery, despite the 1807 US ban on the importation of enslaved Africans. Her book investigates the lives of these individuals, tracing their harrowing journey from modern-day Nigeria to their forced labour in Alabama and their ultimate legacy in the shaping of American communities like Africatown and the quilting circles of Gee’s Bend. […]

[…] Read the review: Hannah Durkin: the Clotilda slave survivors and its lasting legacy […]

[…] Read our review: Hannah Durkin: the Clotilda slave survivors and its lasting legacy […]