Dr Hannah Ritchie’s “Not the End of the World” is a very different book to many recent climate change books, calling for balanced optimism in the often tumultuous discourse about our degrading environment. Ritchie, with a compelling blend of personal anecdotes and robust data, challenges the prevailing narrative of an inevitable apocalypse. She asserts, “doomsday is no better than denial,” reminding us that extreme pessimism is as counterproductive as outright denial of climate issues. Hence, she calls for cautious positivity when tackling such a massive issue.

The 30-year-old’s book is a journey from despair to hope, starting with her own experiences. She shares her initial disillusionment during her studies at the University of Edinburgh, where she was overwhelmed by the gravity of environmental issues without being exposed to positive trends or solutions. This story arc is emblematic of a larger societal trend, where young people are growing up with an acute awareness of the climate crisis, often leading to feelings of doom and helplessness. Even in pop culture, disaster movies such as “The Day After Tomorrow” and “2012” have been hugely successful and, in equal measure, disconcerting.

Read: Intersectional Environmentalist author Leah Thomas on climate change

At the Jaipur Literature Festival, the term “climate anxiety” was discussed by Oxford professor Peter Frankopan while he spoke about his extensive book “The Earth Transformed” and the potential for a ‘sixth extinction.’ Ritchie cites a global survey revealing that a significant majority of young people view the future as frightening, with more than three-quarters thought the future was frightening, and more than half said “humanity was doomed”.

However, Ritchie’s encounter with Hans Rosling’s work marks a turning point in her perspective, introducing her to a world where data-driven optimism is possible. She emphasises the importance of looking at long-term data to recognise the true state of environmental issues, a practice she continues in her role at Our World in Data and as a “misfit scientist” at the University of Oxford.

What is the book ‘Not the End of the World’ about?

The core of Ritchie’s argument lies in advocating for a balanced view. She recognises the severity of environmental challenges but criticises the “doomsday” accounts for being misleading and counterproductive. Such descriptions, she argues, not only distort scientific facts but also lead to merciless paralysis and despair, hindering any effective action.

“Optimism is seeing challenges as opportunities to make progress; it’s having the confidence that there are things we can do to make a difference.”

Ritchie’s book is a call for “urgent optimism” – a belief in the possibility of change grounded in action and evidence. She distinguishes this from blind optimism, stressing the need for active engagement in addressing environmental issues.

‘The world has never been sustainable’

As a result, she begins by confronting a stark reality: “the world has never been sustainable.” This is rather obvious, given that there are eight billion people in the world as of 2024, and resources haven’t necessarily multiplied, but instead have depleted. She explains that true sustainability means not only protecting the environment for future generations but also ensuring current populations can lead good, healthy lives. But that doesn’t mean that it’s already too late.

By delving into the history of human interaction with the environment, Ritchie highlights that even our ancestors caused environmental degradation. This historical perspective sets the stage for understanding the modern challenges of sustainability. She suggests that it is possible to balance human well-being with environmental protection, challenging the notion that these goals are inherently conflicting.

“In 1987, the UN defined sustainable development as ‘meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ […] The world has never been sustainable because we’ve never achieved both halves at the same time.”

For one, she outlines seven key measures of well-being that may change your mind. These include stopping children from dying and reducing child mortality. As recently as 1800, about 43% of the world’s children died before reaching their fifth birthday. Today that figure is 4% – still woefully high, but more than 10-fold lower.

Read: Edinburgh Book Festival: Mikaela Loach walks out over ‘greenwashing’ sponsor

Maternal mortality rates have also plummeted in recent centuries. Until the 19th century, the average life expectancy at birth in the UK was between 30 and 40 years. Now, globally, average life expectancy has increased from around 30 to more than 70 since the start of the 20th century. Food insecurity and famine were common occurrences, and while we still face similar situations, technological advances in agriculture made it much more productive and allowed people to break free from a subsistence lifestyle. In 2020, 75% had access to a water source that was clean and safe – up from just 60% in the year 2000.

In 1820, just 10% of adults in the world had basic reading skills. This changed rapidly over the 20th century. By 1950, more adults in the world could read than couldn’t. Today, we’re closing in on 90%. The United Nations defines ‘extreme poverty’ by using the international poverty line of $2.15 per day. There is good news there too: more and more people are surpassing higher poverty lines – of $3.65, $6.85, or $24 per day. In the past, poverty was always the default. We can build a future where it is the exception.

Reducing population won’t make a difference

Hence, a part of the scientist’s argument revolves around debunking the idea that population control (depopulation) and economic shrinkage (degrowth) are viable solutions – such as that of the ‘One Child Policy’ in China, which has recently been relaxed. Ritchie insists that the world has already passed ‘peak child’ and that reducing the population won’t significantly impact environmental challenges. Similarly, she affirms that degrowth is not a feasible solution, as economic growth can be compatible with environmental sustainability through technological innovation and responsible resource management.

“We’ve seen how dramatically things have improved for humanity when it comes to the first half of the sustainability equation. And that neither depopulation nor degrowth, despite their many advocates, are the solution to the second half.”

Therefore, she believes we can achieve sustainability by embracing technology and innovation, which can decouple economic growth from environmental harm. This approach is rooted in optimism and a belief in human ingenuity, contrasting with the often scaremongering narratives that play into the hands of climate change deniers.

Air pollution can be reversed

The Falkirk-born researcher then doubles down on specific areas of improvement including air pollution. She uses Beijing as a case study, illustrating its journey from being one of the most polluted cities, described as an “airpocalypse,” to significantly improved air quality. Even when I lived in Beijing between 2008 and 2011, the pollution was stifling, to the point of dangerous – and I ended up with chronic bronchitis as a result. Nevertheless, Ritchie highlights Beijing’s transformation, particularly evident during the 2008 Summer Olympics and the 2022 Winter Olympics. This change was attributed to stringent regulations and public demand for cleaner air, leading to a 55% reduction in pollution levels between 2013 and 2020.

The author also discusses the broader historical perspective of air pollution, noting its presence since ancient times. She explains that air pollution is not a uniquely modern problem, with evidence of its effects found in historical texts and even in the lungs of Egyptian mummies. While the issue of air pollution has long been part of human history, recent technological advancements and regulations have led to significant improvements in many parts of the world.

“But air pollution is already killing millions every year and has done so for a long time. Cutting out fossil fuels now would have an immediate impact.”

The Oxford University senior researcher stresses that tackling air pollution successfully, requires getting to grips with its sources and implementing appropriate measures. She cites examples like the reduction of sulphur dioxide emissions in the US and Europe and the Montreal Protocol‘s success in addressing the ozone layer issue.

Ritchie’s message is one of quiet confidence, suggesting that while air pollution remains a significant challenge, historical precedents and recent successes demonstrate our capacity to effect positive environmental change. Still, she urges people to resist the temptation to return to behaviours that seem environmentally friendly but are not. For example, the UK is seeing a surge in popularity for open wood fires and stoves.

Reality check on Paris climate goals

As head of research at Our World in Data, she also confronts the daunting predictions of global warming. She begins with the grim scenario of a world that’s 6°C warmer, focusing on catastrophic consequences such as crop failures, submerged islands, and climate refugees.

She recalls her scepticism during the 2015 Paris climate conference (COP21), where the goal of limiting warming to below 1.5°C seemed unattainable. Though, her analysis of data and policy trajectories led her to believe that staying below 2°C might be a feasible goal. She showcases that with current policies, the world is on track for 2.5 to 2.9°C warming, but if countries honour their more ambitious pledges, this could be limited to around 2.1°C.

There have been significant strides in reducing emissions in many countries, challenging the notion that modern lifestyles are inherently unsustainable. Ritchie spotlights the importance of technological advances and policy interventions, demonstrating that countries like the UK have substantially lowered their emissions while improving living standards.

Her message is not of guaranteed success but of the potential for significant progress. She asserts that while 1.5°C could be out of reach, there’s a realistic path to keeping global warming closer to 2°C, urging collective action and continued commitment to climate policies.

Beyond the oxygen myth

Additionally, she addresses common misconceptions about the Amazon rainforest and the broader issue of global deforestation. She begins by exposing the widely believed claim that the Amazon produces 20% of the Earth’s oxygen, clarifying that while it does produce significant oxygen, it also consumes a comparable amount through respiration and decomposition, rendering its net contribution to the world’s oxygen levels almost nil.

Ritchie reiterates that the primary concern with deforestation, particularly in the Amazon, is not about oxygen production but its impact on biodiversity and climate change. The Amazon, along with other tropical rainforests, houses some of the most biodiverse ecosystems and plays a critical role in carbon storage. She notes that about 20% of the Brazilian Amazon has been lost since the 1970s, but global deforestation rates have decreased since peaking in the 1980s.

The ‘forest transition‘ model is where countries initially lose forest cover as they develop but begin to regain it as they become wealthier and more urbanised. This pattern, however, is not a justification for complacency in addressing deforestation, especially in tropical regions with high biodiversity. What we would need is a rapid and effective action to halt deforestation in the tropics, which means there is a need for tools and international cooperation to support lower-income countries in this endeavour.

Rethinking food sustainability and agricultural practices

In terms of food, there have been ominous headlines about “60 harvests left” for quite some time as well. Ritchie says the specific number doesn’t actually matter, because there is no number. She adds that despite it being unhelpful, “zombie statistics” can weed out the wheat from the chaff, because real activists would be looking at the data rather than sensationalist news. Therefore, we need to find ways of farming that rebuild soils rather than depleting them. She calls for a nuanced consideration of soil health and agricultural sustainability, advocating for evidence-based approaches to addressing genuine environmental concerns.

She focuses on seven practical solutions to global food challenges including:

- Improving crop yields globally

- Eating less meat, especially beef and lamb

- Investing in meat substitutes

- Building hybrid burgers

- Substituting dairy with plant-based alternatives

- Reducing food waste

- Not relying solely on indoor farming.

The main thing she adds is that what you eat matters much more than where it has come from and its carbon footprint.

Biodiversity loss: understanding the real picture

Undoubtedly, there has been a loss in biodiversity, but the degree to the extremeness of the situation has been reconsidered. She corrects a common fallacy, explaining that the World Wildlife Fund’s Living Planet Index (LPI) doesn’t indicate a 68% decline in the total number of animals since 1970, but rather an average change in population size across thousands of species. This metric can be misleading; for example, a significant decline in one population may skew the average, masking increases in others.

“[Losing] 69% of the world’s species within decades would mean we were just inches away from mass extinction. Thankfully we’re still far from that point, and we have more than enough time to turn things round.”

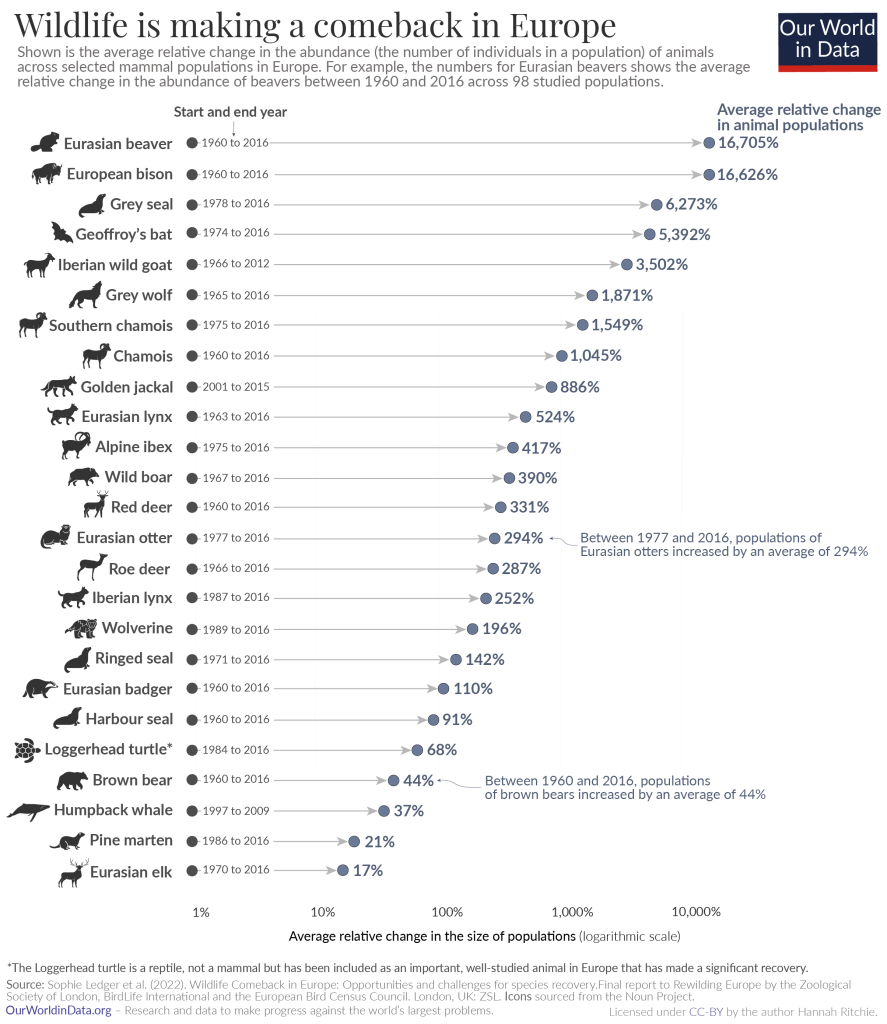

In actual fact, nearly half of mammal and bird populations are actually increasing, which contradicts the dire rhetoric often presented in the media. She points out that while there are certainly species facing accelerated declines and moving towards extinction, a nuanced approach is necessary to comprehend the full picture of global biodiversity.

‘The Sixth Extinction’

Mass extinctions are characterised by the rapid loss of species—specifically, when 75% of species disappear within a relatively short geological time frame, typically around two million years. Historical mass extinctions have been driven by significant changes in the planet’s climate or the chemistry of the atmosphere and oceans.

“I don’t think we’ll put as much direct effort into solving biodiversity loss as our other environmental problems. But what makes me optimistic is that we will reduce it indirectly by tackling all of the other problems.”

Ritchie notes that although 99% of the 4 billion species that have ever lived on Earth are now gone, extinctions are a natural part of evolutionary history. The concern today is the accelerated rate of species loss, far exceeding the natural ‘background rate’ of extinction. For example, since 1500, about 1.4% of mammals have gone extinct. If these rates continue, it suggests a trajectory towards a mass extinction. However, Ritchie thinks that unlike past mass extinctions caused by natural phenomena like asteroids or volcanic activity, the current trend is primarily driven by human activities, meaning we have the power to reverse it.

And there have been some efforts worth mentioning. The recovery of species like African and Asian elephants, blue whales, and European bison, highlight that effective protection policies, habitat restoration, and other conservation measures can make a significant difference.

The biggest threats remain overhunting, agriculture, deforestation, and habitat destruction – all primarily driven by human needs and activities. Hence, the author suggests that by addressing these issues, alongside reducing meat consumption and improving agricultural efficiency, can significantly alleviate pressure on wildlife. However, time is crucial, and every delay increases the risk of irreversible species loss.

Demystifying ocean plastics

She does critique the widely circulated claim from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation that by 2050, there will be more plastic than fish in the oceans. Ritchie points out that this prediction is based on questionable assumptions about both the amount of fish in the oceans and the future quantity of plastic waste.

For one, she explains the difficulty in accurately estimating the number of fish in the ocean. A 2008 study using satellite imagery to measure phytoplankton estimated 899 million tonnes of fish, a number later revised upwards significantly by the same researcher. This revision suggests a much greater amount of marine life than previously thought, indicating that we likely underestimate the quantity of fish in the ocean.

Regarding plastics, Ritchie denounces the linear extrapolation used to predict future ocean plastic levels. She notes that such projections assume no changes in plastic production, usage, or disposal practices, which is unrealistic. Jenna Jambeck, the lead author of a key study on ocean plastics, also expressed scepticism about projecting trends to 2050.

She maintains that the focus on the ratio of plastic to fish is misguided, underscoring that any amount of plastic in the ocean is a problem. She also discusses the origins of ocean plastic, noting that most comes from land-based sources, not marine activities. Contrary to popular belief, only a small percentage of the world’s plastic waste ends up in the ocean, estimated at around 0.3%.

Read: Why appreciating nature is important – Rewild Yourself author Simon Barnes

There are three primary ways wildlife is harmed by plastic addressed in the book: entanglement, ingestion, and physical injury from sharp pieces. Over 340 species, including turtles, seals, and whales, have been documented as entangled in plastics, mostly from fishing gear. Ingestion of plastic by over 230 species can lead to reduced stomach capacity and a false sense of nourishment. Ritchie also notes that plastics can transport invasive species across oceans, disrupting local ecosystems.

Confronting the mistaken belief that plastics are the most significant threat to marine life, Ritchie acknowledges their impact but suggests there are more urgent problems for marine species. She contends that solving plastic pollution is straightforward and does not require new technology, requiring the need for better waste management and a reduction in single-use plastics. But Ritchie condemns the role of wealthy countries in contributing to plastic pollution and stresses the importance of global cooperation and investment in waste management infrastructure to prevent plastics from entering oceans. More responsible practices in the fishing industry and innovative solutions like the Interceptor and other technologies to capture plastics in rivers before they reach the ocean are needed.

‘Empty Oceans by 2048’

The Netflix documentary “Seaspiracy” had claimed that oceans could be empty by 2048, which Ritchie disagrees with. She explains that the concept of a ‘global collapse’ in fisheries science doesn’t mean a total absence of fish but a significant reduction in catch levels. The concern for overfishing is valid, as historically, intensive fishing practices have led to the decline of many fish stocks. However, recent data indicates that the situation is not as dire as once predicted. Around two-thirds of the world’s fish stocks are managed sustainably, indicating a stabilisation of fish stocks in recent years. Continued sustainable fishing practices is an absolute necessity to maintain this balance.

The path to sustainability

In this way, the book goes beyond mere critique, offering a pathway towards sustainability, examining various environmental challenges and proposing solutions. Ritchie’s approach is sophisticated, acknowledging the interconnectedness of different environmental issues and the need for holistic solutions.

Moreover, Ritchie highlights the dangers of complacency and the need for resilience in environmental policies, especially in the face of unforeseen events like the Russia-Ukraine conflict of 2022, which temporarily increased reliance on coal.

“If you are living today, you are in a truly unique position to achieve something that was unthinkable for our ancestors: to deliver a sustainable future.”

Consequently, “Not the End of the World” stands out as a crucial contribution to environmental literature. It navigates the fine line between alarmism and denial, providing a data-driven yet hopeful outlook. She urges young people to think about their “truly unique position” in delivering a sustainable future, and hones in on the fact that we still have options. I recall a visit to the Women of the World Festival last year, where the director, Jude Kelly, asked us whether we felt ‘hopeful’ about the future. When only one hand was raised in the crowd, she responded, “Well, there’s the problem.”

It serves as a reminder that the future is not predestined but is shaped by our actions and attitudes, including the fact that it is possible to hold two opposing views, urging us to adopt a mindset of pragmatic optimism to build a sustainable planet.

[…] Not The End Of The World by Hannah Ritchie (January 9). Data scientist Ritchie flips the script, revealing remarkable progress on global challenges like poverty, hunger, and climate change. Armed with facts and captivating visuals, she argues we’re not doomed, but on track for a sustainable future. This hopeful book empowers you to understand what works, what doesn’t, and how we can all build a better world. Check out our review of “Not the End of the World.” […]