This week, OpenAI, the developer behind the innovative chatbot ChatGPT, admitted the necessity of accessing copyrighted material for creating tools like ChatGPT. This acknowledgement comes amid increasing scrutiny of artificial intelligence firms regarding the content they use for training their products. In response to this situation, we spoke to authors and publishing experts to gauge their opinions on whether the tech companies’ reliance on “fair use” as a defence is sufficiently justifiable.

OpenAI’s acknowledgment of copyrighted material

Chatbots like ChatGPT and image generation tools undergo a training process using a large collection of internet data, a significant portion of which is subject to copyright. Copyright serves as a legal safeguard to prevent the use of someone’s work without their consent.

Just last month, OpenAI and Microsoft, a principal investor in OpenAI and a user of its tools in their products, faced a lawsuit from the New York Times. The suit accused them of engaging in “unlawful use” of the Times’ work for developing their products.

Read: OpenAI refutes New York Times, upholds author fair use

In a statement to the House of Lords Communications and Digital Select Committee, OpenAI revealed that training large language models like its GPT-4, which powers ChatGPT, would be unfeasible without accessing copyrighted materials.

The OpenAI submission said: “Because copyright today covers virtually every sort of human expression – including blogposts, photographs, forum posts, scraps of software code, and government documents – it would be impossible to train today’s leading AI models without using copyrighted materials.”

“Limiting training data to public domain books and drawings created more than a century ago might yield an interesting experiment, but would not provide AI systems that meet the needs of today’s citizens.”

OpenAI

Additionally, OpenAI highlighted that restricting training materials to only those books and drawings no longer under copyright would result in the development of subpar AI systems.

In a blog post on its website responding to the New York Times lawsuit, OpenAI stated on Monday: “We support journalism, partner with news organisations, and believe the New York Times lawsuit is without merit.”

Earlier, the company had expressed its respect for “the rights of content creators and owners.” AI companies often justify their use of copyrighted material by referring to the legal principle of “fair use,” which permits the use of content under specific conditions without the need for the owner’s consent. In its submission, OpenAI asserted its belief that “legally, copyright law does not forbid training”.

What is fair use?

In plain English, “fair use” refers to copying copyrighted material for a specific and “transformative” purpose, like commenting on, criticising, or making a parody of a copyrighted work. These activities can be carried out without the copyright owner’s permission. Essentially, fair use acts as a defence against accusations of copyright infringement against copyrighted products. Therefore, if your use falls under fair use, it is not deemed as an infringement.

What does “transformative” use mean? If you find this term unclear or imprecise, it’s important to know that extensive legal resources have been dedicated to clarifying what constitutes fair use. There aren’t any definitive rules, only broad guidelines and diverse court rulings. This ambiguity is intentional; the judges and legislators who formulated the fair use exception were reluctant to confine its scope. Much like the concept of free speech, they intended for it to be broadly interpreted and flexible in its application.

Fair use and fair dealing laws vary from country to country. Over 40 countries, representing more than a third of the global population, have incorporated fair use or fair dealing provisions in their copyright legislation. The concept of fair dealing originated in England during the 18th century and was formally established in law in 1911. In the UK, the legislation allows for an exception to infringement for fair dealing with a work, specifically for purposes such as private study, research, criticism, review, or summarising in a newspaper. This concept of fair dealing was also adopted in the copyright laws of the countries that were once part of the British Empire, now known as the Commonwealth countries. However, over the last century, the statutes related to fair dealing have undergone significant changes in many of these Commonwealth nations.

Read: Authors launch new lawsuit against Microsoft and OpenAI

Countries outside of the former British colonies, including Taiwan and Korea, have also adopted principles of fair use or fair dealing in their copyright laws.

EU copyright law does not have a “fair use” doctrine equivalent to that found in the United States. Rather, EU legislation specifies a clear list of exceptions to the copyrights held by rights holders, each with its own defined scope. Some of these copyright limitations and exceptions are compulsory for member states to enact, while others can be adopted at the discretion of each individual member state.

At OpenAI’s inaugural developer conference in November, CEO Sam Altman stated that instead of eliminating copyrighted material from ChatGPT’s training dataset, the company is proposing to support its clients by covering legal expenses related to copyright infringement lawsuits.

Check out: Meta AI chief under fire for saying authors should give books for free

Altman stated: “We can defend our customers and pay the costs incurred if you face legal claims around copyright infringement and this applies both to ChatGPT Enterprise and the API.” OpenAI has introduced a compensation program known as Copyright Shield, which is applicable to users of the business tier, ChatGPT Enterprise, as well as developers utilising ChatGPT’s application programming interface. It’s important to note that users of the free version of ChatGPT or ChatGPT+ are not eligible for this program.

Other major players like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon have also extended comparable offers to users of their generative AI software. Additionally, companies such as Getty Images, Shutterstock, and Adobe have implemented similar financial liability protection measures for their image creation software.

What experts told us:

Rebecca Forster, a prominent author, shared her personal experience of having her romance book used for an AI training model without permission. The USA Today bestselling writer said, “Many years ago, I discovered that my book was being used in Google’s AI program without my knowledge. Now I see the devastation to my industry.”

“ChatGPT does not worry me at this point, but I have tested BARD and it is frightening how beautifully it constructs fiction of any genre. If I had it to do over again, I would have aggressively tried to stop Google from using my work.”

Rebecca Forster, USA Today Bestselling author

She expressed regret for the upcoming generation of writers who may wholeheartedly adopt AI and miss out on the unique experience of crafting a work entirely from their own creativity. She adds, “Part of me will always be in the words that AI writes for them.”

On the other hand, Neil Chase said he can see both sides of the argument. The author and screenwriter stated his view on AI’s learning process: “One could say that AI is simply doing the same thing. It may not be directly copying work, but it is using it to learn in order to create its own work (which might be based on the work of others).”

“Whereas many writers will cite their influences openly […] With AI, we don’t know what its influences are, which authors it has used for its learning algorithms, or the extent to which it uses those authors’ words.”

Neil Chase, Author and Screenwriter

Joshua Lisec, an acclaimed ghostwriter, passionately supports adopting technological advancements: “The publishing industry needs to stop looking backwards and start looking forward. Embrace the future, because it’s already here.” The “So Good They Call You a Fake” author even says he would offer his book to train the model without needing his permission.

Read: Authors’ pirated books used to train Generative AI

While Paolo Danese, a technology strategist, highlighted the multi-layered nature of the debate and the fact that AI could “democratize content creation,” adding that “The use of copyrighted material to train these systems without explicit consent or compensation to the original authors raises significant ethical and legal concerns.”

“[As] a proponent of equitable and inclusive publishing, I believe in the necessity of compensating authors for their contributions, even when used for training AI. The notion that a crackdown on copyright infringement would doom these tech companies is exaggerated and self-serving.”

Paolo Danese, technology strategist and innovator

Sol Nasisi, founder of Booksie, discussed the importance of author consent having already blocked OpenAI and other AIs from consuming their author’s content for training its systems. He said: “authors should have the ability to control how their work is used and also to set the terms. Some writers may decide to provide it for free while others may set a price on the use of their intellectual property,” but he believes there may be a more transparent exchange in the future.

What Mastodon users say

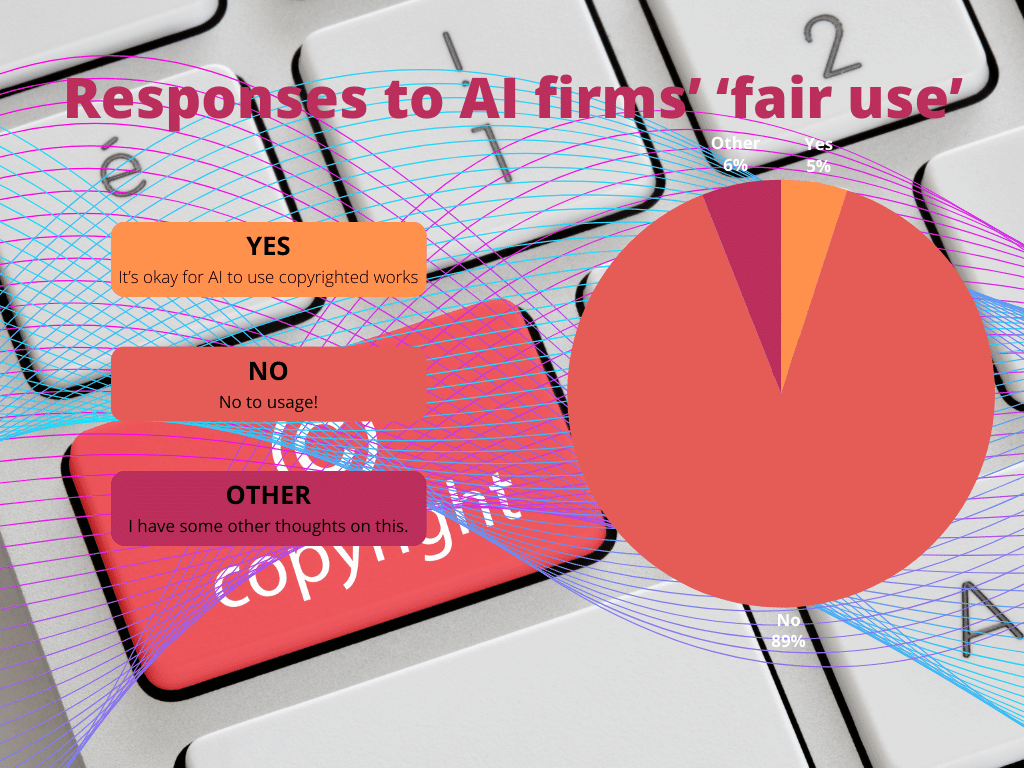

To measure public sentiment, we turned to Mastodon users, with 89% expressing the view that using copyrighted material without proper attribution and credits is not fair use, while 5% disagreed. Some argued that the concept of fair use is murky and may not apply well to AI models. Others emphasised the importance of not using AI models for commercial purposes without proper licensing.

The debate continues, with opinions ranging from advocating for technological progress to stressing the need to protect authors’ rights. Finding a balance between innovation and respecting copyright laws remains a challenge in this fast-changing technological arena. All we know is that creatives are in the firing line of this ‘brave new world.’

[…] Read: Is it ‘fair use’ for OpenAI and AI firms to use copyrighted works? […]

[…] More from our Friday opinion pieces: Is it ‘fair use’ for OpenAI and AI firms to use copyrighted works? […]